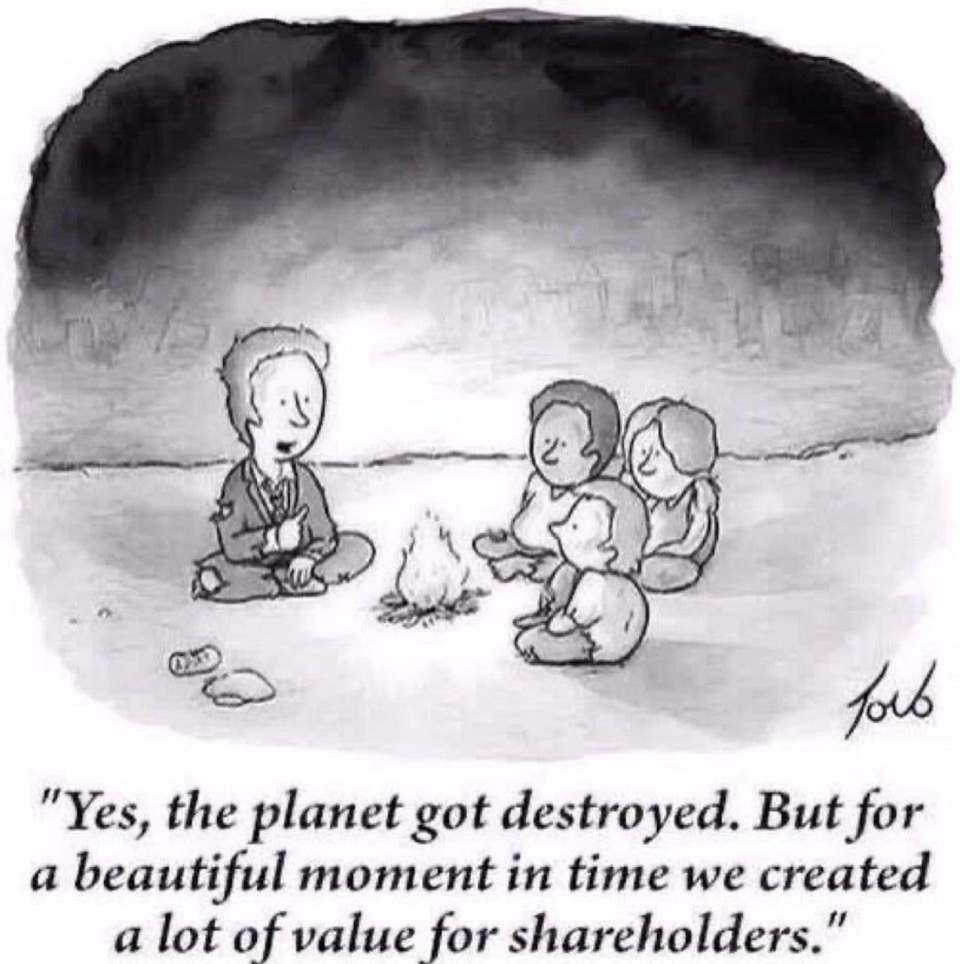

how, in the kynicism of Diogenes of Sinope, the laughter about philosophy itself became philosophical. I wanted to show how in the pantomimes and wordplays of the philosopher from the tub, the Gay Science was born, which saw the earnestness of the false life recur in the false earnestness of philosophy. With this, the satirical resistance of conceptually informed existence against the presumptuous concept and against a teaching that has been blown up into a form of life begins. Socrates mainumenos embodies in our tradition an impulse giver who denounces idealistic alienation at the moment of its emergence. In this, he went so far as to use his whole existence as a pantomimic argument against philosophical inversions. Not only did he react extremely sensitively and coarsely to the moral absurdities of higher civilization; he was also the first to recognize the danger embodied in Plato, that the school will subjugate life, that the artificial psychosis of “absolute knowledge” wants to destroy the vital connection between perception, movement, and understanding, and that, in the grandiose earnestness of idealistic discourse, nothing other than that earnestness returns with which life most lacking in spirit stifles itself with its “cares,” its “will to power,” and its enemies, “with whom one cannot fool.”

In Diogenes’ antiphilosophical jokes, an ancient varient of existentialism takes on a form Heinrich Niehues-Pröbsting has called, with a very happy phrase borrowed from Gigon, the “kynical impulse.” He means the sublation of philosophizing in mentally alert life oriented simultaneously toward nature and reason. From this source springs the critical existentialism of satirical consciousness that cuts through the space of respectably presented European philosophies as if it were its secret diagonal.

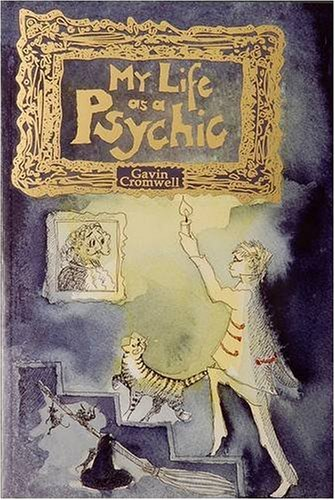

Imagine you are born with a curse.

The curse works like this: what you do in your life, the relationships you have, the thoughts you think, the things you do — in effect the content that makes up how you view your life is rendered immaterial by the fact that you were produced for a totally different reason.

The function which makes you its object is indifferent to all the content that makes up and occupies your body, your life, your time.

If you want to put this idea into images you can think of the film The Brave Little Toaster (1987). The BLT is made to toast bread, his relationship to the lamp, the vacuum, etc. is not relevant to the toaster’s function. No one needing toast cares if the toaster is friends with the lamp.

If you want to put this curse in a science fiction frame think of Never Let Me Go (2010).

This Curse.

This terrible curse.

Is the same curse that afflicts art writing.

When I say art writing I mean it in it’s extended form.

The horrible truth is that each of these individual elements is forced to exist but its content is of hardly any consequence.

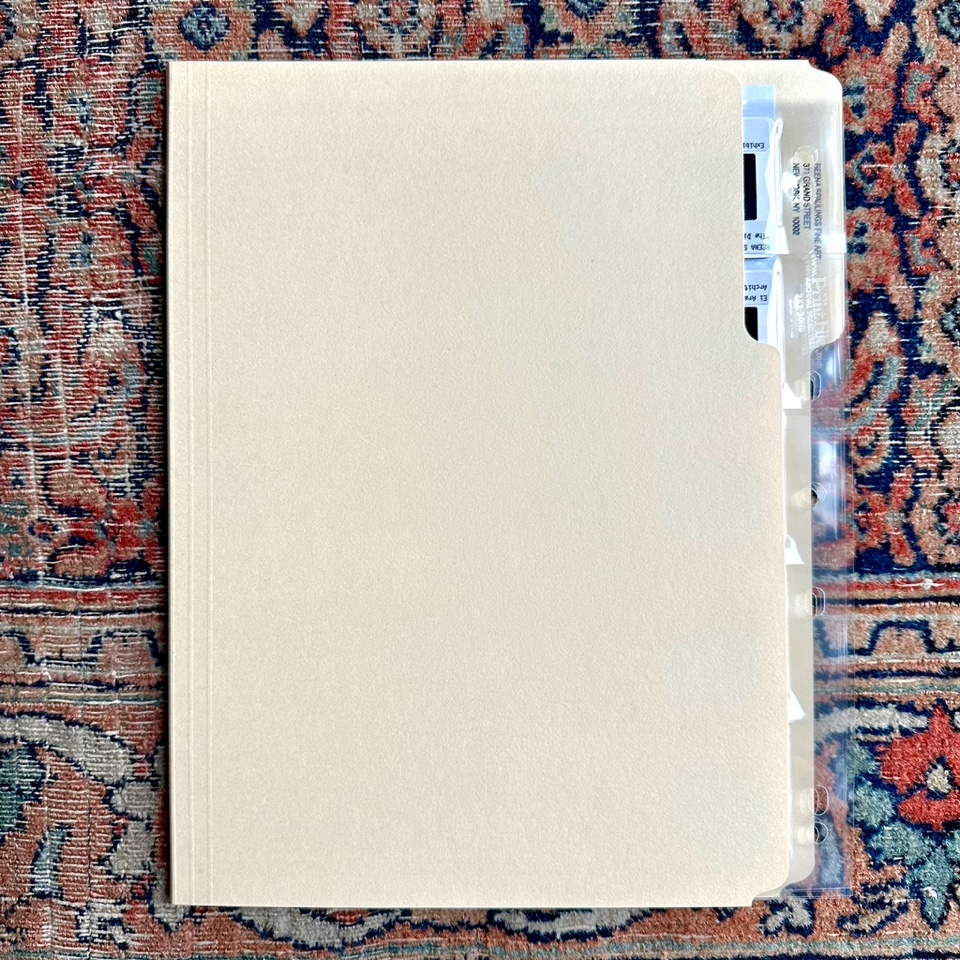

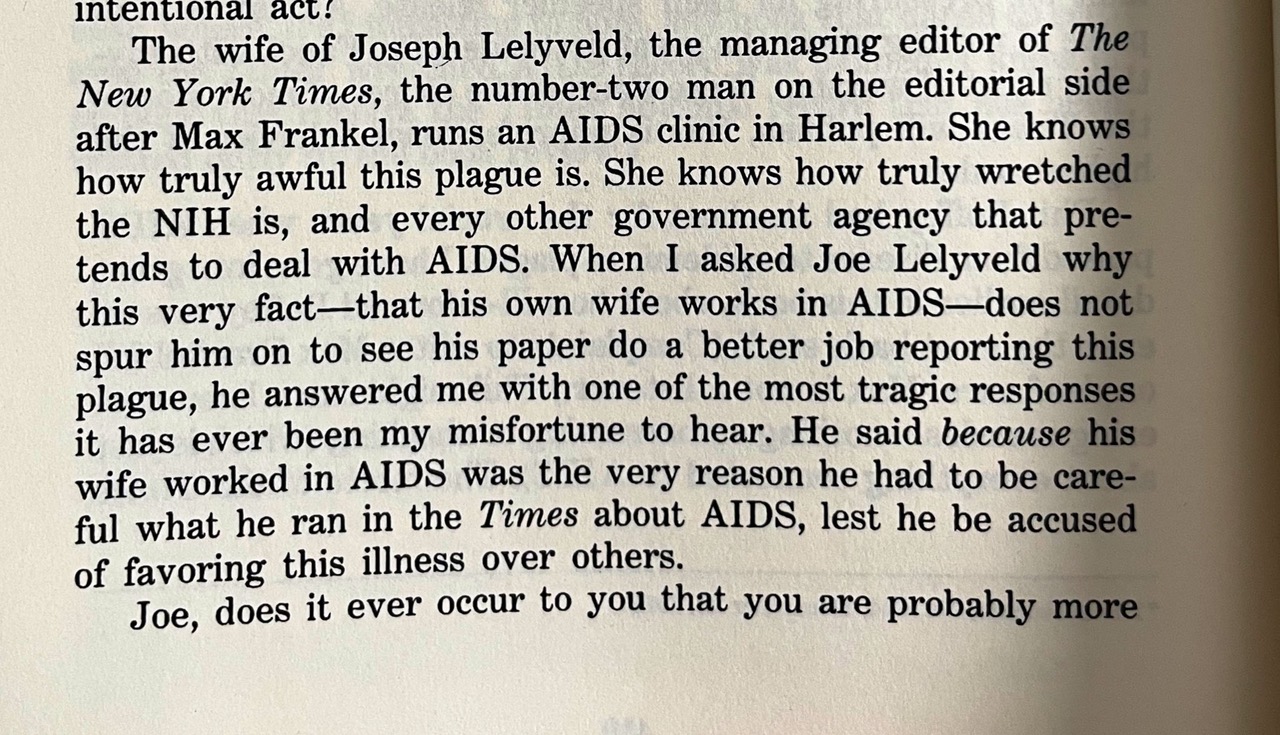

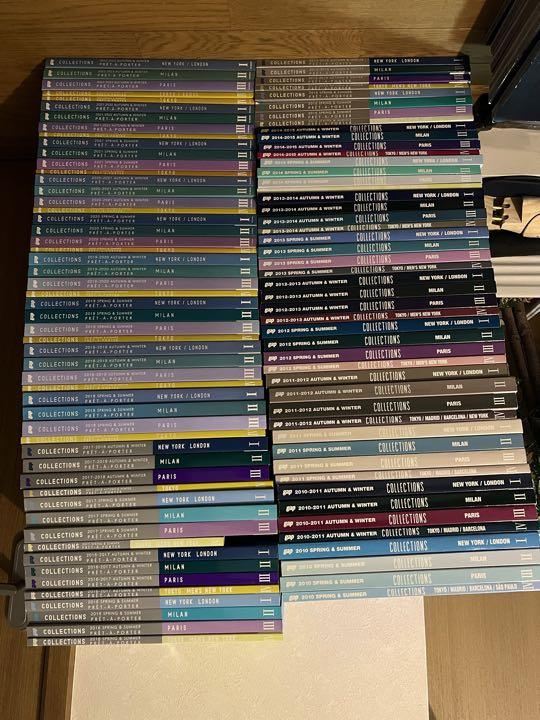

It’s one thing when NSCAD is asking a small group of relatively noncommercial artists to present their work as a kind of lived research. It is another thing entirely for an artist in their 30s to have a catalog the size of a phone book published. Something is up.

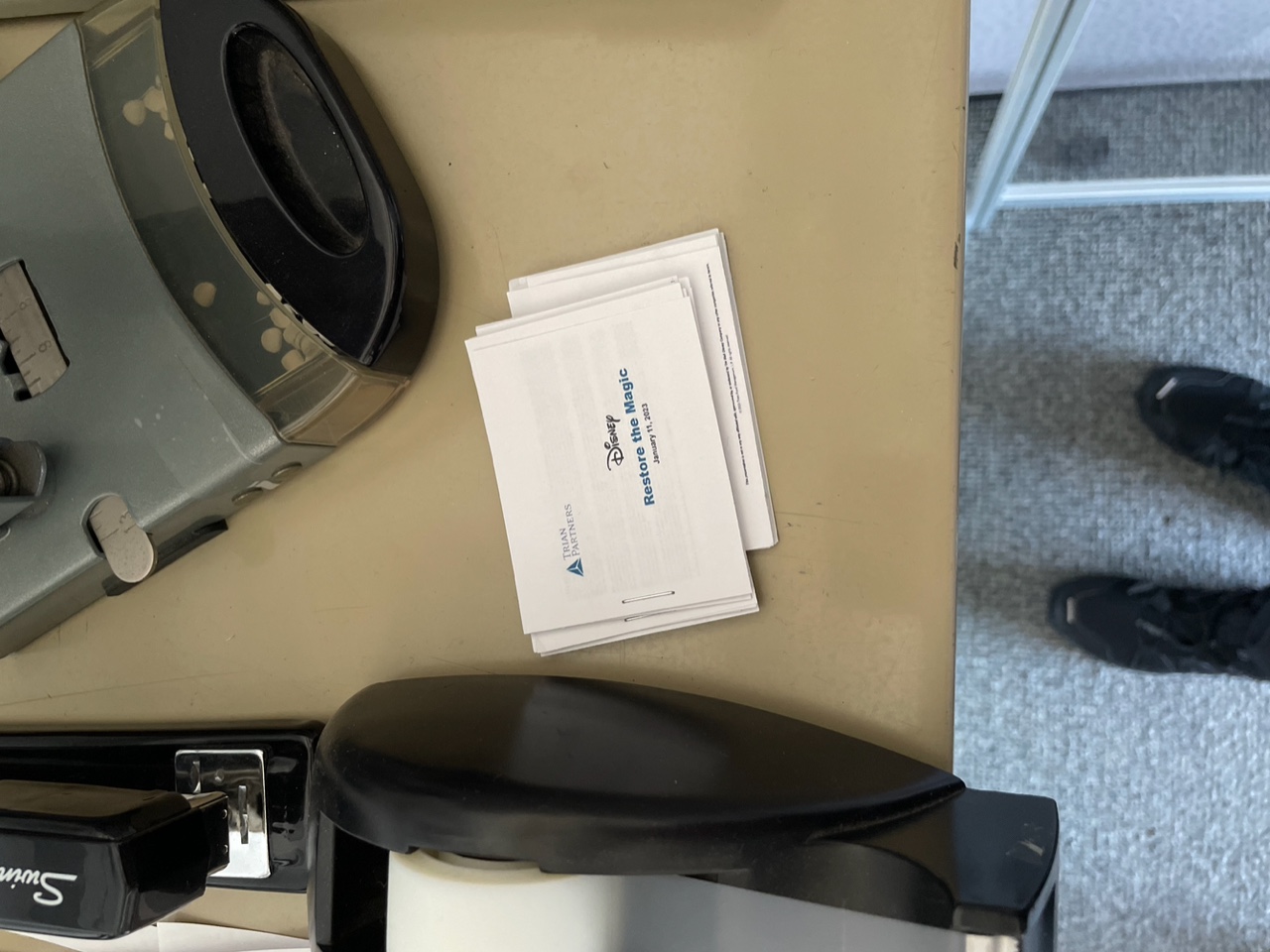

The complete works of Sturtevant fit in one thick book, she lived until her 80s. How many books we do we need for the ongoing career of a contemporary painter? The simple thing here is this: galleries saw how publication produced a way for people with nearly entirely peripheral careers, like Simone Forti for example, to become part of art history.

What will sell your formalist paintings better than having the appearance of critical appreciation and gravitas behind it.

This might seem reductive. But that’s the thing: this can drive you even if you don’t acknowledge that it’s driving you.

The future of art publishing is illiteracy.

Paper bricks designed to be noticed and left closed.

But if you consider every book whose producer didn’t have the courage to acknowledge the truth of this situation you are looking at a field that has at worst produced flip books and at best produced tiny sculptures. If we were looking in these places for the writing, we are looking in the wrong place. What obtains is something closer to mid-century modern furniture — not so uncommon that it can’t be found, but not available at Target. An index of taste and interest but that’s about it.

In answer to the question: “Why Do It?” the only answer I have is you should do it if you want to, if these are the kinds of works you want to make or you should do it for your friends. Because friendship is, if anything, the only truly good thing left in the arts.